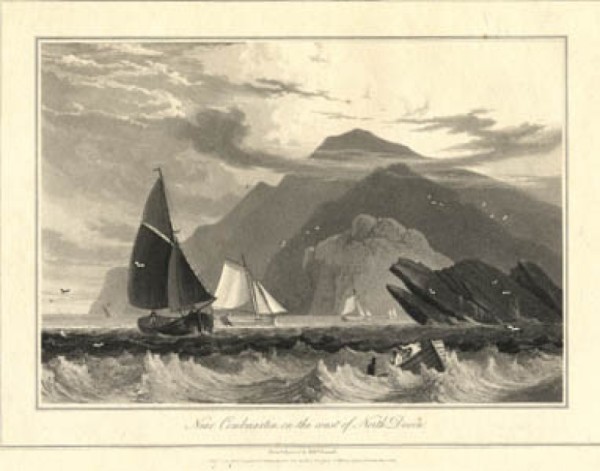

Near Combmartin, on the coast of North Devon (1814, )

William Daniell| Repository | Library | Shelf |

|---|---|---|

| Devon | West Country Studies | L SC0412 |

Illustration Reference

SC0412

Location

CD 8 DVD 1

Publication Details

Publisher

Scope and Content

Ayton, Richard: A voyage round Great Britain, undertaken in the summer of the year 1813 and commencing from the Land's-End, Cornwall. London: Longman & Co and W. Daniell, 1814. Vol 1. pp. 50 -52.We at length arrived opposite to a point of land, from whose base the rocks project so far into the sea, that in doubling them we were exposed to the full force of the tide. Here we remained stationary, and as if spell-bound, for ten minutes, the men straining with all their might, and, in their rage, startling us with their profane wishes that they and the boat might go to the bottom. In the oral chart of the boatmen along the shore this terrible point is emphatically denounced as Pull-and-be-damned Point. Perseverance had finally its just reward; we doubled the point, and immediately entered into the quiet little cove of Combe-Martin, sheltered from wind and tide, and with nothing to disturb our contemplation of the varied scenery around us. We had rowed about four miles from Ilfracombe, in which interval the coast, though broken and indented, preserves a continued line. At Combe-Martin, a deep and narrow glen, which extends to a considerable distance inland, separates the great chain of cliffs, and terminates in the sea. This chasm opened to us a view of uncommon richness and fertility, swelling over the masses of black rock, which, on each side of the bay, form the base of the land. Above them the hills rise to a great height, and are cultivated to their summits. Cultivation can make even a flat country pleasing, but it is singularly delightful to see mountains thus softened and subdued, and their sharp ridges and sudden peaks shaded with trees and yellow with corn. Vegetation on the steep sides of these heights does not destroy their majesty, for it has none of the trimness of art about it, but is as wild and fantastic in arrangement as the surface over which it is spread. The whole seems like; the sole work of nature; and one might fancy that the same bold hand which piled the unhewn rocks below, had scattered over the rising hills their various decoration.Round the whole coast we had seldom seen a gap in the cliffs that was not filled by a fisherman and his boat, and the little inlet of Combe-Martin is fully occupied by a few boats on the beach, and by a group of cottages beyond, sufficiently inartificial in appearance to harmonize with the general scene. They are situated at the bottom of the glen, which on each side is overhung by hills of the same fertile and romantic character as those which skirt the bay.We found that one of the cottages was a public-house, with no promise on the outside, but furnished with plenty within, and a very sensible landlady, who maintained that nothing was superior to a good breakfast, which she regarded as the foundation on which everything useful or agreeable in the business of the day was to be raised. We were precisely in a state to coincide with her in opinion, and to admit, that no circumstances, however elevated, can make us forget, for any length of time, that we have a stomach. Love and jealousy may have great control over us, but in the long run we are slaves to nothing so much as to bread and butter.In five minutes all the male population of the village had assembled about us at our meal; and ale, a great leveller, soon determined that there should be no secrets between us. When we had satisfied all their questions, they revealed to us that they gained a subsistence by fishing and by piloting vessels in the Bristol Channel. They felt themselves somewhat scandalized, however, by these simple pursuits, and reverted with pride to those days when a little honest smuggling cheered a man's heart at Combe-Martin with a drop of unadulterated gin. "But these are cruel times," they observed, "and the Lord only knows what we shall be obliged to give up next." They were occasionally assisted, they told us, by a wreck; but this was a very uncertain casualty, and scarcely to be hoped for twice in a winter. We had frequent conversations on this subject with various boatmen during our voyage, and always discovered that they consider it in no degree a moral offence to plunder a wreck. When a vessel is once driven ashore, they look upon it as justly lost to the owners, and sent to be fairly scrambled for by all those who will hazard their lives for the spoil. They pay no more respect to the construction of the law in this case, than to that abominable despotism that would deprive them of their gin. Amongst themselves, a man who had robbed a vessel of property to the amount of fifty pounds might pass for a very honest fellow; but if he were known to have stolen a pocket handkerchief on shore, he would be shunned as a thief. They talk of a good wreck-season as they do of a good mackarel-season, and thank Providence for both.When we returned to our boat the tide had turned and the wind abated, so that we proceeded along very smoothly and pleasantly. For three leagues to the eastward of Combe Martin the coast is even more vast than that which we had just passed. Some of the cliffs are computed to be a thousand feet in height, and they are so steep, that when we were not many yards from their base we could distinguish sheep on the ridges and projections at their summits. These sheep appeared like white specks, so very minute that we should not have observed them at all had they not been pointed out to us by the boatmen, nor have believed that they were animals of any kind had we not perceived that they moved. We were contesting the matter with the men, with our eyes intently fixed on a cluster of the white specks, when they suddenly vanished, and we then granted at once that they could not be daisies. The cliffs are generally covered with short russet grass, and in parts tufted with shrubby oak; but the rocks are frequently seen bursting through this surface, and at intervals all vegetation is arrested; the rocks appear rising in fragments over fragments, and the whole front looks like one tremendous ruin. The changes which have taken place on the face of this coast are of no recent date, and have not been effected by the common force of the sea, or by any of the slow causes which act at present on the surface of the earth, but by some sudden and extraordinary convulsion. Some of the cliffs preserve deep traces of a violent shock, and where the edges of the rocks are disclosed the strata are seen broken and overturned; but in a general view of the coast, though the ruin still appears, it appears in a state of reparation, and the sharp peaks and rugged indentations are partially smoothed and rounded by earth, and garnished with a sprinkling of vegetation. This coast is considerably loftier than any part of the north coast of Cornwall, but it has not the same wild and terrible grandeur, the same dismal, desolate gloom, which was always associated in our minds with shipwrecks and storms. It is at intervals only on the coast of Devon that the rocks burst forth; but on the coast of Cornwall, league after league is marked by one dark line of rock, never interrupted by a patch of earth, but parted by a wide chasm, faced also on each side with rock, and again renewed, and still in rock. Both coasts appear to have been shattered by some tremendous concussion, but in the one the effects have been gradually softened by time, while in the other the confusion is still fresh and unreformed, the ruggedness unvaried and untamed.[Text may be taken from a different source or edition than that listed as the source by Somers Cocks.]

Format

Aquatint

Dimensions

165x238mm

Series

S40. DANIELL William (text by AYTON, Richard): A VOYAGE

ROUND GREAT BRITAIN UNDERTAKEN IN THE SUMMER OF THE YEAR 1813 AND COMMENCING FROM THE LAND'S END, CORNWALL.

ROUND GREAT BRITAIN UNDERTAKEN IN THE SUMMER OF THE YEAR 1813 AND COMMENCING FROM THE LAND'S END, CORNWALL.

Places

Counties

Subjects

Dates

1814